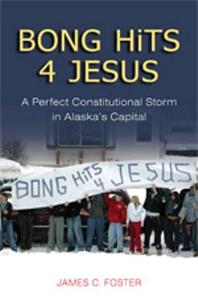

BONG HiTS 4 JESUS: A Perfect Constitutional Storm in Alaska's Capital by James Foster (2011, University of Alaska Press, 373 pp., $29.95 PB)

Oregon State University professor and student of judicial politics James Foster tells the tale of a case that has helped shape First Amendment jurisprudence in the exceptionally sticky milieu of student free speech rights and schools' rights to accomplish their educational missions. And while there is a plenty of fine-toothed examination of the high court's legal reasoning in Morse v. Frederick, as the case came to be known, as well as related cases, there is a lot more to BONG HiTS 4 JESUS than dry textual analysis.

When, on the first page of the first chapter of the book, the author references Japanese film director Akira Kurosawa's classic 1950 film Rashomon, the reader begins to get an inkling that this is going to be something of a ride. And so it is.

Foster sets up a story of conflicting narratives in a conflicted town in a conflicted time. Juneau, Alaska's capital city, is an isolated town in an isolated state, a liberal island of blue in a sea of red, a small town where the protagonists in local conflicts are likely to run into each other at the grocery store. That social and political context, and the hostilities it engendered, helped turn what began as a local imbroglio into a problem that could only be decided by the Supreme Court.

If Joseph Frederick had been less of an authority-challenged troublemaker, or if Principal Morse had had a better administrative style, the whole affair could have been handled as little more than a tempest in a teapot. Foster excels at explaining why that wasn't to be and how a disciplinary interaction between an educator and a student ends up as constitutional question before the highest court in the land.

Aside from the interpersonal and community context of the conflict and the case, Foster also excels at explaining the legal context, discussing at some length a line of cases about student rights running back to the seminal 1969 case, Tinker v. Des Moines School Board, in which the court famously held, in Justice Abe Fortas' words, that "Students… do not leave their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the school house gate." That case involved students wearing black arm bands to protest the Vietnam War.

But, as Foster makes abundantly clear, Fortas' stirring -- and oft-cited -- proclamation was actually stronger than the court's own ruling in Tinker, where it held that political ("symbolic") speech could not be constrained as long as it did not interfere with the educational mission of the school. And as his examination of the handful of key post-Tinker cases relating to student rights demonstrates, the bright and shining rule of Fortas' formulation has been quickly and relentlessly chipped away at by less friendly Supreme Courts.

Some of those cases were not First Amendment cases, but Fourth Amendment ones. The elements they had in common with Morse were the scope of students' rights and adults' fears about drugs. In those two cases, conservative courts approved the use of warrantless, suspicionless random drug testing, first of athletes and then of any students involved in extracurricular activities. As in other realms of law, the Supreme Court in those cases created a drug war-based exception to the Fourth Amendment when it comes to students, or, as Foster puts it, a "Fourth Amendment-Lite."

Through close examination of oral arguments and the different written opinions in Morse, Foster shows that the same concerns about student drug use weighed heavily on the minds of the justices, so much so that they were moved to decide against Frederick's free speech rights. The Roberts court was more afraid of a nonsense message that could -- with some contortions -- be construed as "pro-drug," than it was of eroding the freedoms enshrined in the First Amendment.

BONG HiTS 4 JESUS is not a book about drug policy, but it is one more demonstration of the way our totalizing, all-encompassing war on drugs has deleterious effects far beyond those of which one commonly thinks. Really? We're going to trash the First Amendment because some kid wrote "bong hits" on a sign? Apparently, we are. We did.

There are some dense thickets of legal exegesis in BONG HiTS 4 JESUS, and the book is likely to be of interest mainly to legal scholars, but Foster brings much more to bear here than mere eye-watering analysis. For those concerned with the way the war on drugs warps our lives and our laws, this book has much to offer.